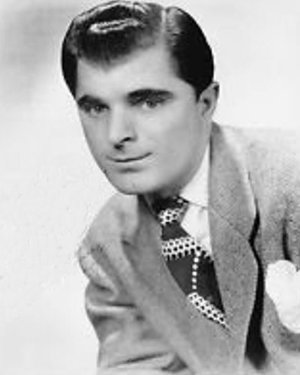

Don Darcy

aka Don D'ArcyJohnny DarcyJohn Arcesi

-

Birth Name

John Anthony Arcesi -

Born

February 11, 1917

Sayre, Pennsylvania -

Died

April 13, 1983 (age 66)

Palm Springs, California -

Orchestras

Charlie Barnet

Johnny Bothwell

Rudy Bundy

Sonny Dunham

Dick Gasparre

Joe Marsala

Hal McIntyre

Art Mooney

Boyd Raeburn

Joe Venuti

Baritone Don Darcy had one of the more interesting careers of any band vocalist. Darcy began singing with swing orchestras in the mid-1930s but veered into progressive jazz in the mid-1940s. Breaking out as a solo artist in 1947, he struggled at first but finally managed to attract attention in 1952 when he adopted his birth name as a stage name and began an unusual act that made the national headlines for its odd public relations stunts. Darcy ultimately failed to find success, however, and by the mid-1950s he had faded into the background. He continued writing music and singing into the 1970s.

Born to Italian immigrant parents in Sayre, Pennsylvania, hometown of singer Russ Columbo, Darcy grew up idolizing the popular vocalist. Darcy was so obsessed with becoming a band singer like Columbo that he ran away from home at age 14 and headed to New York, where he worked various jobs and slept on park benches, hotel roofs, and in subways while he pursued his ambition. He sang as a freelance band vocalist during the mid-1930s, recording with Lud Gluskin in 1934 and Louis “King” Garcia in 1936. He also worked for Charlie Barnet and sang on local radio before joining Joe Venuti’s orchestra in 1937, where he stayed for four years.

As Darcy told it, he earned the job with Venuti after approaching the bandstand one night and bragging that he could sing like Bing Crosby, to which Venuti, a known jokester, replied that he couldn’t possible sing like Crosby because he had hair and Crosby was balding. Taking it as a challenge, Darcy shaved his head the next day to resemble Crosby’s balding pate and showed up again that night. Venuti hired him. Whether the tale is true or not is unknown, as apparently many stories circulated about pranks played between the two men, including one that told of Venuti trussing up Darcy and suspending him over a theater pit with a tarpon and pole, which Darcy said was untrue.

Darcy, whose name was sometimes written D’Arcy, left Venuti in May 1941 when the leader revamped his orchestra. He joined Dick Gasparre and then Rudy Bundy before ending up in Joe Marsala’s new band in August 1942. In January 1943, he joined Sonny Dunham, where along with fellow vocalist Dorothy Claire, he provided color to what was an otherwise lackluster band. While with Dunham, Darcy married his first wife, Carolyn Frazier, in September.

In February 1944, Boyd Raeburn raided Dunham’s band, taking Darcy, Claire, and four of Dunham’s key sidemen for his progressive jazz orchestra. Darcy proved popular with Raeburn, staying more than a year. He was reported to have received over seven thousand letters from Detroit-area fans when his rendition of “Prisoner of Love” was aired on local radio. He left the band in April 1945, replaced by David Allen, and briefly became part of Hal McIntyre’s orchestra that month as it prepared to travel overseas. After failing to pass USO requirements for the trip, however, he looked for radio work and managed the Studio Cafe in New York before joining Art Mooney’s band in June, where he was known as “Johnny” Darcy.

In early 1945, Darcy divorced Carolyn and in November married Evelyn Quinet. Saxophonist Johnny Bothwell, a former Raeburn bandmate, served as best man, and Bothwell’s wife, singer Claire Hogan, who had worked with Darcy in Mooney’s bands, served as maid of honor. When Bothwell put together an orchestra of his own in early 1946, Darcy left Mooney to join him. With Bothwell, Darcy finally began to come into his own, catching the attention of both critics and audiences. One Down Beat reviewer noted that “he sings well everything he does and has an unusually intelligent grasp of phrasing.” Darcy placed tenth in the category of male band singer in Down Beat’s annual poll that year, far up from the 23rd he’d placed the year before.

Post-Band Years

Darcy stayed with Bothwell through the end of 1946, remaining in New York when the leader went west to Kansas. Going solo, he recorded two songs on the Embassy label early in 1947. He also recorded on Century Records in 1950. Plagued with financial and marital difficulties, Darcy worked his way to Honolulu, where in 1952 he was heard singing at a house party by agent Bert Richman. Richman decided that Darcy’s voice was worth the investment and brought in publicity man Ed Schofield to help. They arranged a Capitol Records contract for him under his real name, John Arcesi.[1]

Richman and Schofield put a great deal of energy into promoting Arcesi, cooking up two notorious publicity stunts which one Down Beat writer called “the most startling space-grabbing stunts since P.T. Barnum.” The first stunt revolved around the release of Arcesi’s recording “Wild Honey.” They sent jars of honey to disk jockeys as a gift to promote the song, and Schofield set up a photo op with a model dubbed Miss Wild Honey. Apparently, the full extent of the photo op was unknown to her—or perhaps Arcesi ad-libbed when he dumped a jar of honey over her head—and the model sued, eventually settling out-of-court for $750 in late 1955.

The second stunt involved hiring an aspiring starlet named Ariel Ames to attend Arcesi’s show at the Thunderbird in Las Vegas on November 9, 1952, just before the release of his song “Lost in Your Love.” The woman pretended to go into a trance when he sang the number and had to be hospitalized. The national wire services picked up the story, and it made headlines across the country. Newspapers published a picture of the supposedly unknown woman, which prompted her grandmother to identify her. A “hypnotic therapist” examined her, curing her by having Arcesi sing the same song again in her hospital room, which “woke” her after 39 hours in the trance. This cure also made the national news. When Capitol sent out copies of the song to disk jockeys, the record sleeves reproduced clippings of the incident and gave warning that playing the song could cause some members of the listening audience to become hypnotized.

While the public might have fallen for such theatrics, show business and music industry insiders didn’t, and the stunt became a source of amusement in the trade press. Columnist Earl Wilson attended Arcesi’s first New York performance just before Christmas at the French Casino. When no one fell into a trance, he asked a “spokesperson,” who told him that “a wholly unscheduled and spontaneous trance will occur at the second show.” Billboard reviewer Bill Smith attended the second show and reported that a woman in the front row gave Arcesi a very expensive ring after he’d finished singing his infamous trance number, apparently hypnotized in the same manner as was the starlet in Las Vegas. For added flair, the woman was “East Indian” and wore a turban. The stunts had their intended effects, however, and Arcesi suddenly became a hot commodity. Sales picked up on his recordings, and Hollywood studios tapped him to star in a film based on the story of Russ Columbo, his idol, the story rights to which, coincidentally, belonged to Richman and Schofield.

In addition to such publicity stunts, Arcesi’s performances also featured numerous gimmicks, much to the dislike of reviewers. He wore odd clothing, made exaggerated movements and sang in an odd manner. In the end, it was all for naught. While Arcesi made the headlines and was briefly in the spotlight, he never followed up with any recordings that sparked the public’s interest, making only one other single for Capitol before the label dropped him. He recorded on the Kem label later in 1953, backed by Nelson Riddle’s orchestra, and though he received good reviews, it went nowhere. He worked the night club circuit all throughout 1953, his most notable engagements being in early March when he missed his opening night at the Boulevard after spending the night in jail thanks to non-support charges filed by his ex-wife, Evelyn, and in December when he followed Frank Sinatra at the French Casino in New York.

In late 1953, Arcesi dropped the gimmicks and changed both management and booking agencies, but by then it was too late. His career as a pop singer was effectively over. For his part, he knew that the gamble might not pay off, saying “it takes more than publicity stunts to get to the top and stay there long enough to make something of it.” He added: “I have to be able to put something into a song that leaves a lasting impression on the listener. You can’t do that with gimmicks and trick sound effects.” He compared himself with Columbo. “Russ sang with simplicity and deep, honest sincerity. That’s the way I want to be known—or not at all.”

Arcesi spent the latter part of his life writing songs and producing other recording artists, occasionally singing and recording under pseudonyms. In 1972, he released an offbeat psychedelic album under the name “Arcesia”[2] which has since become a collector’s classic for those who enjoy odd music.

John Arcesi passed away in 1983, age 66.[3]

Notes

Sources

- Simon, George T. The Big Bands. 4th ed. New York: Schirmer, 1981.

- The Online Discographical Project. Accessed 6 Dec. 2015.

- “Night Club Reviews: Frank Sebastian's, Culver City, California.” Billboard 8 Jan. 1938: 20.

- “The Reviewing Stand: Joe Venuti.” Billboard 31 Dec. 1938: 67.

- “The Reviewing Stand: Joe Venuti.” Billboard 16 Mar. 1940: 13.

- “Vaudeville Reviews: RKO Palace, Cleveland.” Billboard 22 Feb. 1941: 24.

- Herzog, Buck. “Reviews of the New Films.” The Milwaukee Sentinel 22 Feb. 1941: 6.

- “Andrews Gals Big 24G in Pittsburgh.” Billboard 22 Mar. 1941: 20.

- “New Band, New Outlook For Venuti.” Down Beat 15 May 1941: 2.

- “Biagini Managing New Venuti Band.” Down Beat 15 Jun. 1941: 1.

- “One the Air: Dick Gasparre.” Billboard 17 May 1941: 12.

- “Orchestra Notes.” Billboard 11 Jul. 1942: 21.

- “On the Air: Joe Marsala.” Billboard 5 Sep. 1942: 20.

- “Dunham Minus One Canary; Claire Gets Male Songmate.” Billboard 30 Jan. 1943: 22.

- “Vaudeville Reviews: Oriental, Chicago.” Billboard 19 Jun. 1943: 16.

- “Orchestra Notes.” Billboard 26 Jun. 1943: 26.

- “Tied Notes.” Down Beat 1 Nov. 1943: 10.

- “On the Stand: Sonny Dunham.” Billboard 25 Dec. 1943: 35.

- “Pop Record Reviews: Sonny Dunham.” Billboard 5 Feb. 1944: 60.

- “Strictly Ad Lib.” Down Beat 15 May 1944: 5.

- “Song Plug Hits Mulholland Hard.” Billboard 23 Sep. 1944: 19.

- “Lost Harmony.” Down Beat 1 Mar. 1945: 5.

- “Night Club Reviews: Hotel Sherman, College Inn, Chicago.” Billboard 17 Mar. 1945: 24.

- “Raeburn Recording Session Presents Trade Sidelights.” Billboard 31 Mar. 1945: 103.

- “Music as Written.” Billboard 21 Apr. 1945: 21.

- “McIntyre Readies For Overseas Jaunt.” Down Beat 1 May 1945: 1.

- “Strictly Ad Lib.” Down Beat 15 Jul. 1945: 1.

- “John Darcy Marries.” Down Beat 15 Dec. 1945: 1.

- “Band Poll.” Down Beat 1 Jan. 1946: 16.

- “Vaudeville Reviews.” Billboard 2 Mar. 1946: 40.

- “Music as Written.” Billboard 27 Apr. 1946: 26.

- “Bothwell Trains Before Tour.” Down Beat 20 May 1946: 2.

- “Slicker D'Arcy.” Billboard 22 Jun. 1946: 20.

- “Bothwell Leads Boff Well Combo.” Down Beat 15 Jul. 1946: 2.

- “Advance Record Releases.” Billboard 31 Aug. 1946: 31.

- “Advance Record Releases.” Billboard 16 Nov. 1946: 30.

- “1946 Band Poll Winners.” Down Beat 1 Jan. 1947: 20.

- “Diggin' the Discs.” Down Beat 15 Jan. 1947: 20.

- “Music—As Written.” Billboard 11 Jan. 1947: 16.

- “Advance Record Releases.” Billboard 11 Jan. 1947: 34.

- “Trade Tattle.” Down Beat 10 Mar. 1948: 22.

- “Music as Written.” Billboard 27 May 1950: 18.

- “Arcesi, Carr Ink Capitol Wax Pacts.” Billboard 5 Jul. 1952: 45.

- “Music as Written.” Billboard 11 Oct. 1952: 27.

- “Girl Who Blacked Out During Song Recovers Senses.” Lodi News-Sentinel [Lodi, California] 12 Nov. 1952: 7.

- “Capitol Hits Novel Way to Launch Disk.” Billboard 29 Nov. 1952: 20.

- Smith, Bill. “Caught Again: French Casino, New York.” Billboard 20 Dec. 1952: 16.

- Wilson, Earl. “Man about Town on Gay Broadway.” Beaver Valley-Times [Beaver, Pennsylvania] 23 Dec. 1952: 4.

- Emge, Charles. “I'll Need More Than Publicity Gimmicks To Succeed: Arcesi.” Down Beat 14 Jan. 1953: 2.

- “Strictly Ad Lib.” Down Beat 11 Mar. 1953: 3.

- “Music as Written.” Billboard 21 Mar. 1953: 32.

- “Second Visit Is Key Problem for Would-Be Stars.” Billboard 18 Jul. 1953: 20.

- “Popular Records.” Down Beat 23 Sep. 1953: 12.

- “Music as Written.” Billboard 10 Oct. 1953: 22.

- “Strictly Ad Lib.” Down Beat 4 Nov. 1953: 3.

- “Strictly Ad Lib.” Down Beat 31 Dec. 1953: 3.

- “Worth $750.” Spokane Daily Chronicle [Spokane, Washington] 4 Jan. 1956: 1.

- “California Death Index, 1940-1997”, database, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:VPZF-MJ7 : 26 November 2014), John Anthony Arcesi, 13 Apr 1983; Department of Public Health Services, Sacramento.

- “United States Social Security Death Index”, database, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:JGQV-5X3 : 11 January 2021), John Arcesi, Apr 1983; citing U.S. Social Security Administration, Death Master File, database (Alexandria, Virginia: National Technical Information Service, ongoing).

- “United States Census, 1930”, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:XH84-S6Y : Tue Oct 03 03:33:37 UTC 2023), Entry for Toney Arcesi and Ignats Arcesi, 1930.